The crow photographer Raphael Fourau went off to discover the climbing possibilities of Iceland. An ethereal athletic trip to the country of ever changing weather.

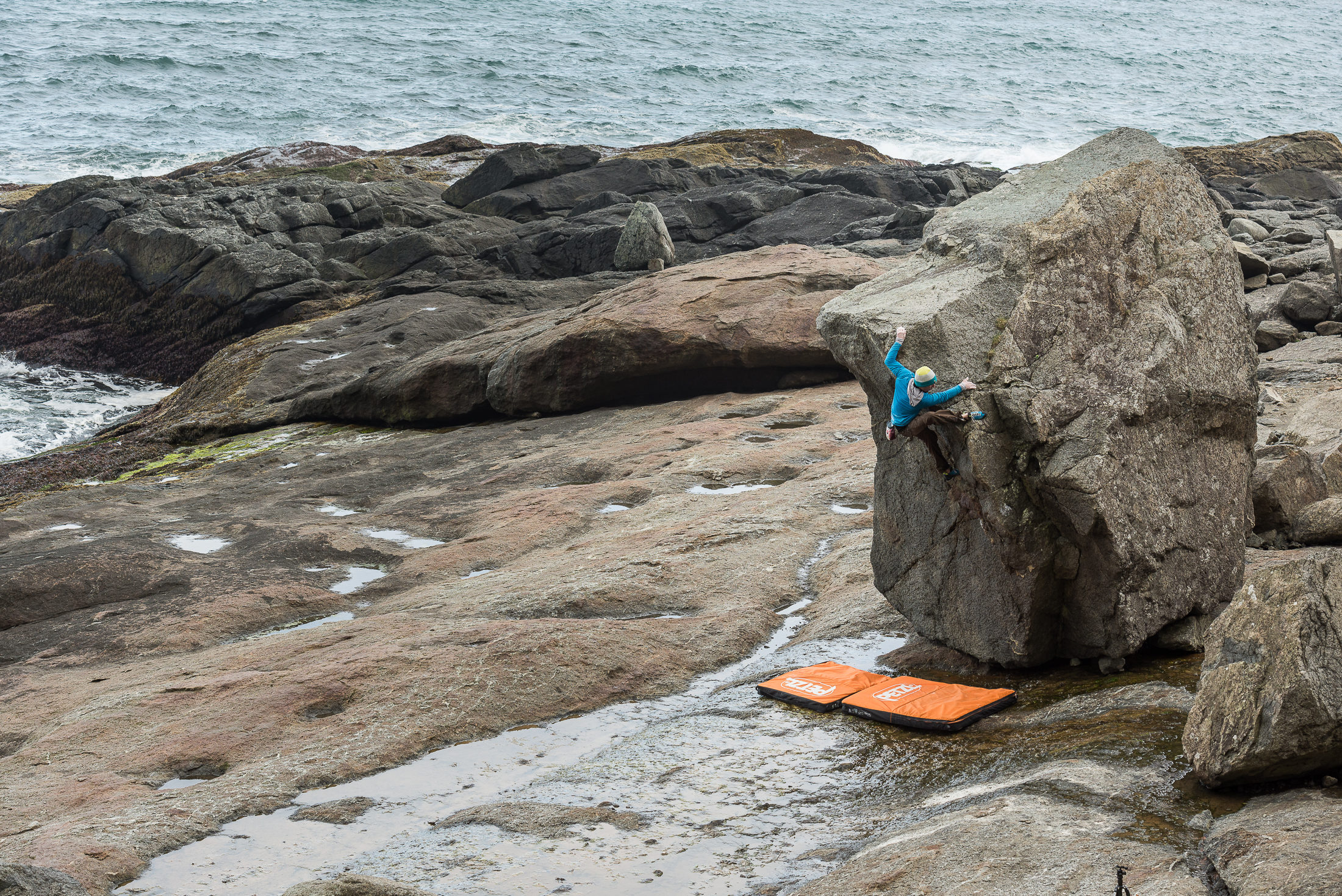

The wind has been battering our tents since our arrival on the island a few hours ago. The thought of getting out of the sleeping bag and abandon our last stronghold against the cold is not really enchanting us but we will have to deal with it. Stuck between the ocean and an imposing rock massif, one of the most remote climbing spots of the planet is awaiting us out there. In the very heart of the Viking territory, at the north-east tip of Iceland, the Vestrahorn boulder chaos is probably the most incredible site we have ever seen… Sheer excitement is in the air, and despite the wind and the cold we are ready to tackle this totally crazy spot! This time, I think we have just found what we came for in Iceland: a new approach of climbing. To get off the beaten path to consider climbing with a new perspective, leaving a large part to the unknown.

CThis time, the adventure was daring, we were aware of it. Iceland does not let itself be tamed so easily and we did not really know what we were going to stumble upon. The island is well- known among hikers, photographers, surfers and nature lovers but very few climbers take a shot at it. Probably due to the whimsical weather which may threaten your trip in a minute or more simply due to the absence of significant cliffs. These things do not really matter, we are seven European climbers ready to live an Icelandic experience. Florence, Danielle, Adrien, Gérôme, Mathieu, Thomas and I… eager to criss-cross the country during two weeks, crammed into our four-wheel drive, in search of new climbing spots!

Our arrival at Keflavik airport takes place in a timeless atmosphere, bathed in a stunning light at three in the morning. A photographer’s dream… quickly obliterated by a violent return to reality: the airline company lost most of our luggage. There we are, stuck in Reykjavik for a few days, wandering around the streets and bars of the city. We quickly feel really low. No matter what happens, we have to bounce back, with or without luggage, so we take the decision to hit the road. The call of remote mountains is too strong. We are told by the Icelandic climbers we contacted before our departure to meet close to the most equipped cliff on the island: Hnappavellir. Our faces stuck to the windows of our four-wheel drive, we eventually discover this Iceland we have been dreaming about for months and we understand fairly quickly what is awaiting us. The Earth is steaming from every hole, the rain seems to blend with a huge invisible blaze. Glaciers suddenly show up along a curve of the road and die in the ocean as they unfold. Everything seems surreal and out of scale. Iceland shows its real face to us: a fragile natural balance in which volcanoes and glaciers, fire and ice coexist.

Our trip looks like an endless day. We took the decision to leave in June, a time of the year with the slimmest chances of rain and continous daylight. It is a precious advantage which allows us to climb until exhaustion, without caring about the rest. After those few painful days, our discovery of the Hnappavellir cliff is truly bulimic. We switch from one area to the other, trying as many routes as we can; our only limit is the skin of our fingers damaged by the abrasive basalt. One more time, we are stunned by what we find out: the cliff turns out to be an endless basaltic tongue oscillating between ten and thirty meters high and several kilometers long. The playground is just enormous.

Most of our luggage is still wandering in plane holds. We must then be creative. We improvise makeshift harnesses and share the ropes between the climbers and the photographer. It does not really matter, as long as we climb… this is the most important. Little by little, reflexes resurface. We pretty quickly spot significant lines, routes which seem harder than others. Temptation is too strong. We leave the comfort zone of an easy playful climb and push our limits. Alternately, climbers devote themselves to their respective project. Icelandic climbing is

unveiling itself to us: demanding slabs, on which each placement is carefully thought, each balance precarious. Climbers fall then repeat the moves and attempt to find the right body language which will allow them to unknot the score. Smiles resurface on faces, we are in our element. The setting is totally unknown, the scale is upset but the rules remain the same, we know them

We are rapidly faced with the difficulties of climbing in Iceland. The cold and humidity force the climbers to carefully handle the resting periods between their attempts: leaving some time for the body to recover but not getting too cold to avoid the numbness of fingers. The bottom of the routes is a sheer swamp, the ocean not far away, drown in the horizon. Florence and Gérôme are the most experienced climbers, they are used to this adaptation exercise. Towards the end of the afternoon, they both send the route they had chosen at the beginning of the day. A solid 8a+ repeated only a few times. As a wink of fate, it is at this very moment that Thomas and Danielle show up with our bags, dropped a few minutes earlier by a passing bus. We find again the comfort of our warm clothes. It is already late but climbing at this latitude has some surreal quality. Continuous daylight is propelling us in a daze. Gérôme takes advantage of it and sets off to open an unclimbed route. He quickly spots the movements, the effort is suiting him. Barely back on the ground, he announces me that he is going to attempt to send it tonight. It is 10 in the evening, maybe later. It does not matter, I run to my static rope. A few minutes later, Gérôme is clipping the belay.

In the evening, we meet our Icelandic friends in a wooden hut built with their own hands at the bottom of the cliff. Among them, Eyþór Konráðsson and Valdimar Björnsson, two Icelandic climbers very active in the development of climbing on their island. The following day is the opportunity to discover the spot with the locals. Valdimar is keen on showing us one of his projects: a route he has been working on since several years. Gérôme is the only one who is able to take up such a challenge. The previous day has been exhausting, his fingers are swollen, scratched and bloody. No matter what it takes, temptation is too strong. He puts on his climbing shoes, ropes himself up and sets off in the route. One attempt leads to another and the sense of emulation is growing. All the climbers are gathered at the bottom of the route to encourage them. Gérôme eventually sends the route in a final push, therefore freeing ‘Kamarprobbi’, which becomes the hardest route on the island to this day. The conversations with the locals are amazing, their motivation is truly impressing us. One evening, Eyþór tells us about a remote boulder spot located at the south-east tip of the island. The site is still confidential, there is no existing topo but Eyþór meticulously lists all the rocks in a corner of his mind. More than two hundred of them have already been opened but the potential remains huge. Our eyes glimmer. We have already heard about this boulder spot, called the Vestrahorn chaos. We do not have enough information to go there on our own but it turns out that without being aware of it, we have been climbing since a couple of days with the main actors of this new site.

We have now been following Eyþór’s four-wheel drive since more than one hour in the direction of Höfn, a remote fishermen’s village. He promised us to stop at a hot spring and a warm meal. Promise kept, and we hit the road again, clean and our stomach filled with the local speciality, the Icelandic lobster. It is 11 in the evening but daylight is still there, tiredness too. Since the beginning of the trip, we have been pushing our limits, the cold is taking its toll on the mood, the unstable weather is inciting us to make the most of each climbing day, forgetting the pain of worn fingers and sore muscles. Nobody talks in the four-wheel drive, we truly feel exhausted and secretly dream about a comfortable campground and running water. The four- wheel drives race on the dirt road then suddenly make a turn towards the ocean. The vision is

surreal, our minds have a hard time fully realizing it, we are now driving right in the middle of the ocean, crossing a laguna stretching over a few hundred meters. Nobody talks but the faces speak for themselves… No boulder in the horizon, only the ocean as far as the eye can see and a misty severe-looking massif.

I have a hard time believing that a four-star campground is awaiting us somewhere in this setting. We hit the road again on a chaotic dirt road before spotting other vehicles parked at the top of a hill. Not far away, a group of people are gathered around a huge stone chimney, a remain of a Viking past. On the other side of the hill, the expected show is there, a huge chaos of boulders all around us… We pitch our tents right in the middle of nowhere and set off to meet the Icelandic climbers grouped around the fire. A comfortable campground can wait. We have a big day tomorrow: we have just found what we came for in Iceland…’