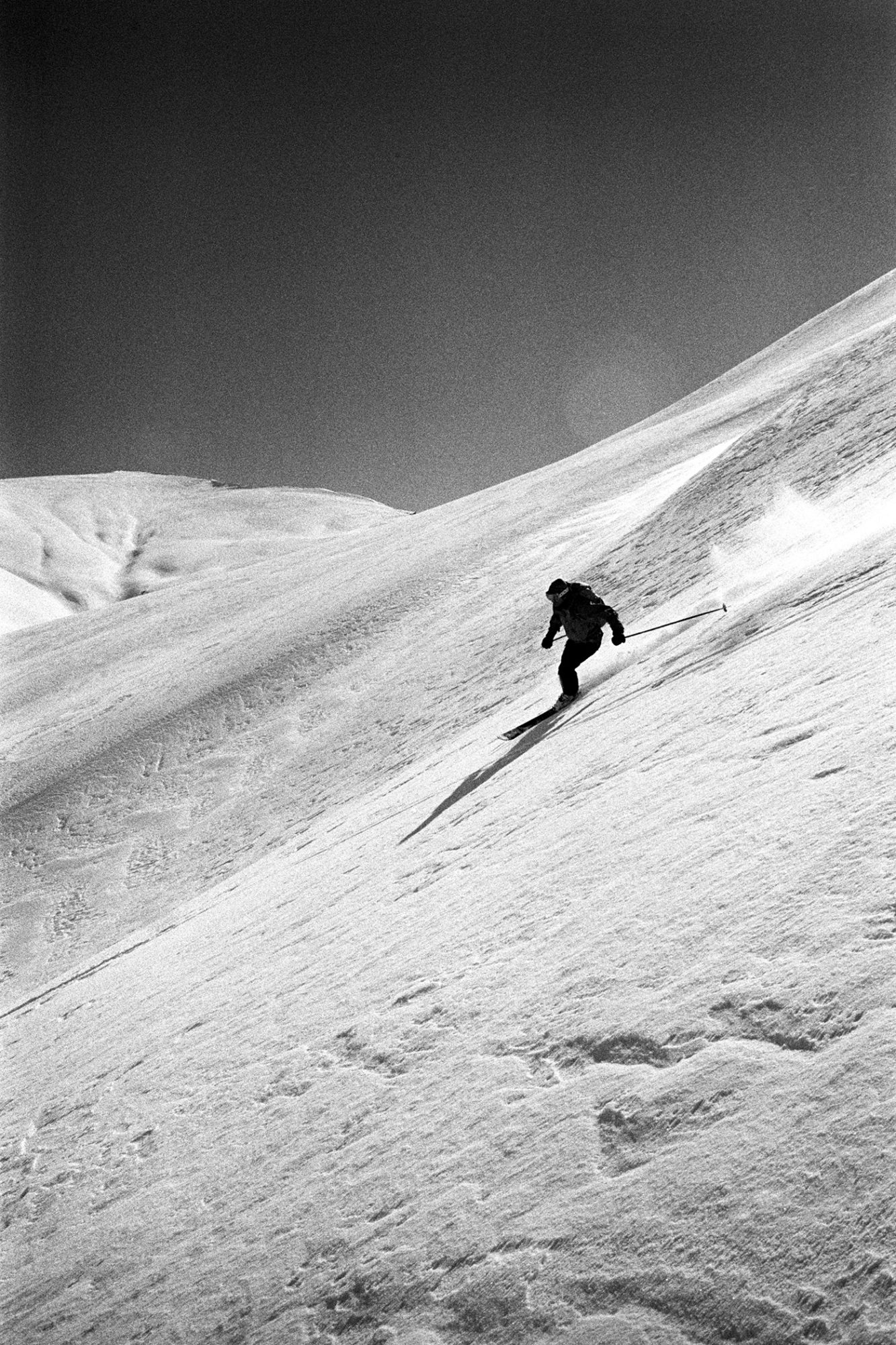

The rest of our day, us deprived ones, finishes on a majestic descent. Over 1000m of vertical and several kilometres of wacky races in dreamlike spring snow. When you get a glide that’s so light, so delicate, the slightest push transfers instantaneously, without any worry, any restraint. We really open it up, accelerating until the skiing becomes more like a flyover. Moments of levitation with Christophe Delaage, an old accomplice from Chamonix… Our spirits soar to the tune of the skiing itself and our voices escalate, irresistibly, into whoops of joy. We pin it all the way down to the village crossing fences and gardens, trying not to squash the delicate umbel clusters poking out of the snow. We all gather at the foot of the village and our faces beam, revisiting the magical moments we’d just shared, enjoying mouthfuls of tea and handfuls of dried fruit. When the snow is so forgiving, skiing really is like child’s play.

On the walk back, Mt. Kazbek is outlined in the distance. Its diminutive neighbours accentuate its own prominence. Taking its western name from the eponymous village of Kazbegi, the Georgians call it Mkinvartsveri, meaning “glacier” or “mountain of ice” and the Ossetians, Urskhokh, the “white mountain”. A little Chamoniard insight: it was first climbed on the 1st July 1868 by François Devouassoud and his famous client, Englishman Douglas William Freshfield as well as two of his compatriots Adolphus Warburton Moore and Charles Comyns Tucker. One month later the guide from the hamlet of Les Barrats and his three cronies would set foot on the eastern sub-peak of Elbrus at 5621m- just 21 metres lower than the western peak. This historical foray puts things back into perspective with our ultralight skis, breathable clothing and P4 rated sunglasses.

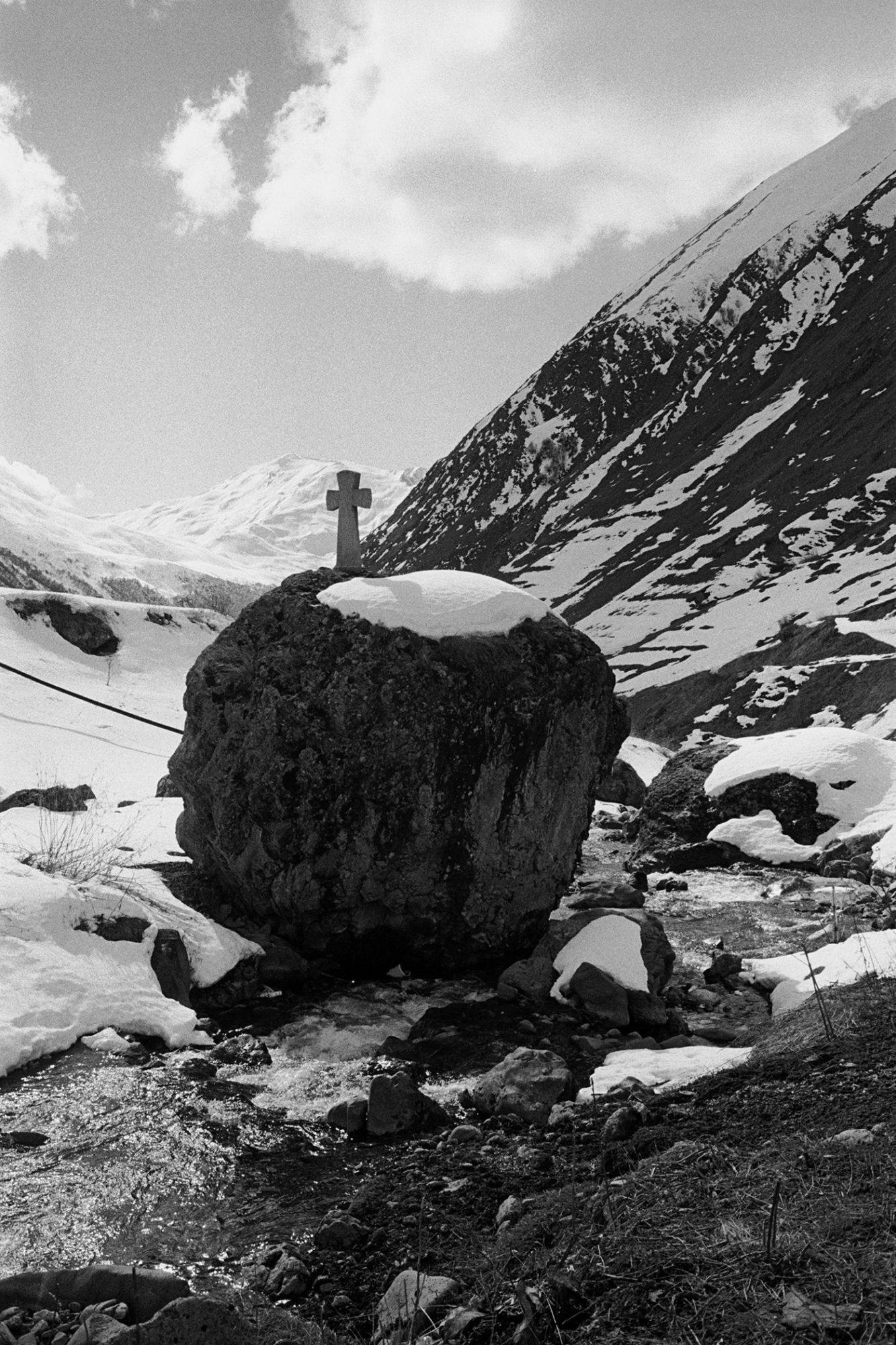

The next day we take our skis up to one of the peaks on the gigantic crater, which Mt. Kazbek is the culminating point of. After passing by the Tsminda Sameba Church once again, a big plateau takes us to a pass marked with a cross, guarding a stunning view over the Gergeti glacier hanging off Mt. Kazbek. The summit seems to be within our reach but in the mountains distances can be deceiving; we’d surely need a bivouac before being able to reach the slopes under the peak. Saying that, it was never our objective anyway, which is good news because it looks like a bit of a slog. Instead we decide to climb a little peak on a steep slope holding snow that doesn’t feel very reassuring at all. It’s a bit unpredictable so we space ourselves out to improve our chances of staying safe. The snowpack holds fine and we reach the summit without too much trouble.

In front of us extends a long plateau with the adjoining flank to our line of approach leading to a huge untouched face. The whole way along, a never-ending cornice blocks our way through so we have to search for a chink in this perfect wave of snow sculpted by the wind. Christophe and I decide to skirt along it for a hundred meters or so, to reach a decent entry point to the perfect looking powder field. Then, taking it in turns, we plunge towards the white horizon in front of us. The snow is an absolute delight and our turns instinctively widen out. We play with the terrain at full throttle, flowing down to the bottom of the slope as if in suspension. Once we check the smiles are all in order, it’s straight onto the next totally untracked but less steep slope down towards the Tsminda Sameba. We take our skis off and cross the big meadow next to the sanctuary. There’s a monk looking out over the mountains in full meditation so we carry on past him and sit down on our bags to enjoy the incredible view in the afternoon sun as we wait for the rest of the group.

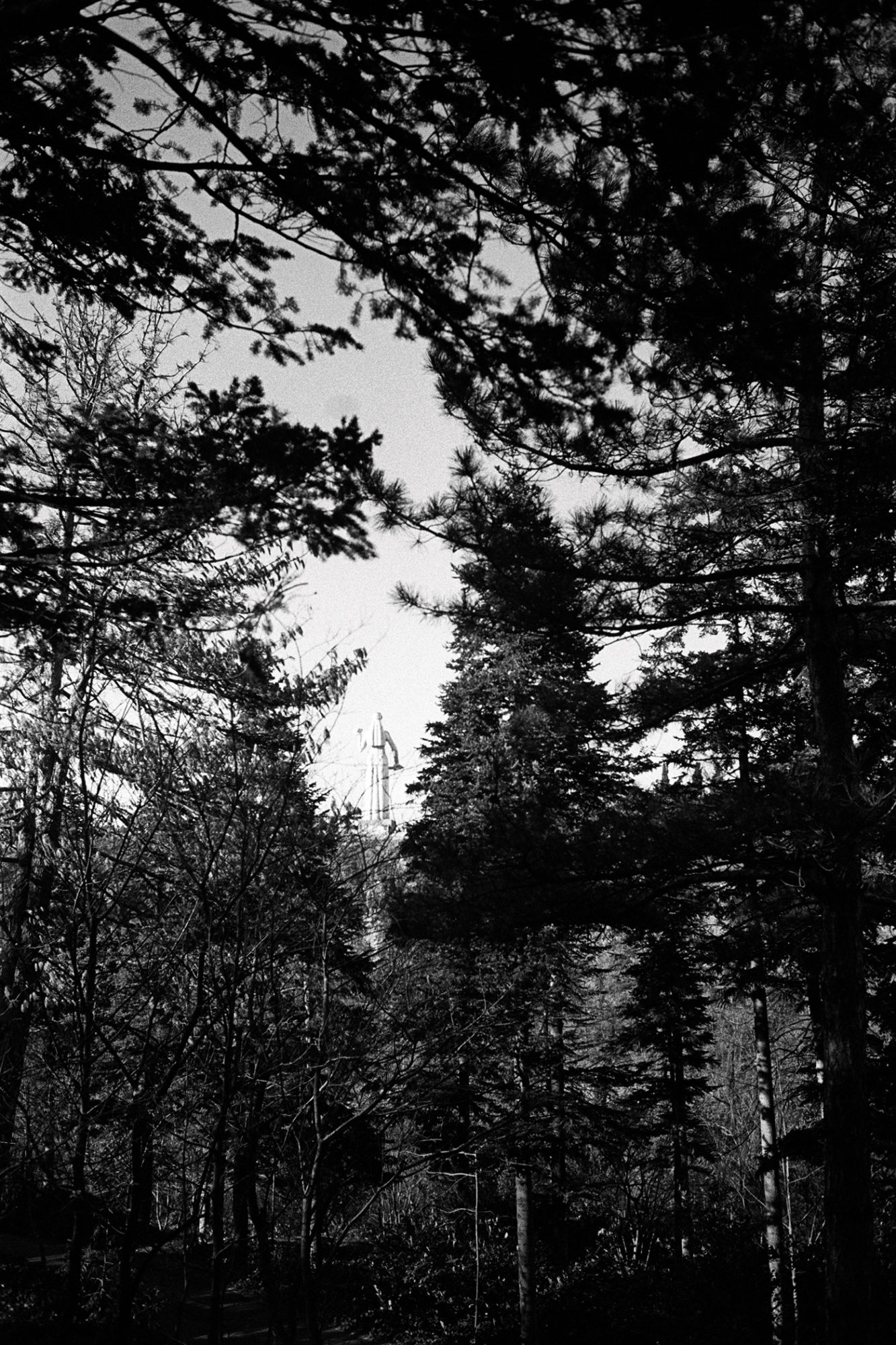

The time comes to say goodbye to the Nazi family and get back on the road to Gudauri. On the way through we pass a famous mosaic that’s several dozen meters long and dedicated to Russo-Georgian friendship. This monumental fresco built in an arc shape at the side of the road is captivating, as much for its positioning on the edge of an abyss as for the multi-coloured arrangement of propaganda that’s past its sell-by date. The history of the two countries is played out on either side of the fresco while a gigantic female character takes centre stage, filling the mould of Soviet communism. This naïve art does have a certain charm and you might even allow yourself to be taken by Soviet nostalgia if you can forget about the red terror that harshly affected Georgia. Stalin, Georgian by birth from the village of Gori, did nothing to spare his own people in his dictatorial madness.

Back in Gudauri, we spend two days using the ski lifts to access a big bowl full of pristine runs. Once you get over the col by mechanical means, short ski tours take you to a big cirque where there are loads of little peaks. A few hundred meters of vertical alone gives you lots of different options: steep or more mellow slopes, narrow couloirs or wide powder fields, you are free to make your choice depending on how you feel that day. As for the conditions, the big blue sky remains stuck over the Caucasus and the snow, despite the deep heat, stays in good shape until the beginning of the afternoon. The way back brings us through a pretty little valley with a stream coming out onto a small, seemingly abandoned village. Even though many of the buildings have been left to rack and ruin, at closer inspection, a good quarter of the houses still have people living in them. A man in rags, dog by his side, is dragging bundles of sticks on a cart. Crows caw in the birch trees that provide shade for a little cemetery…

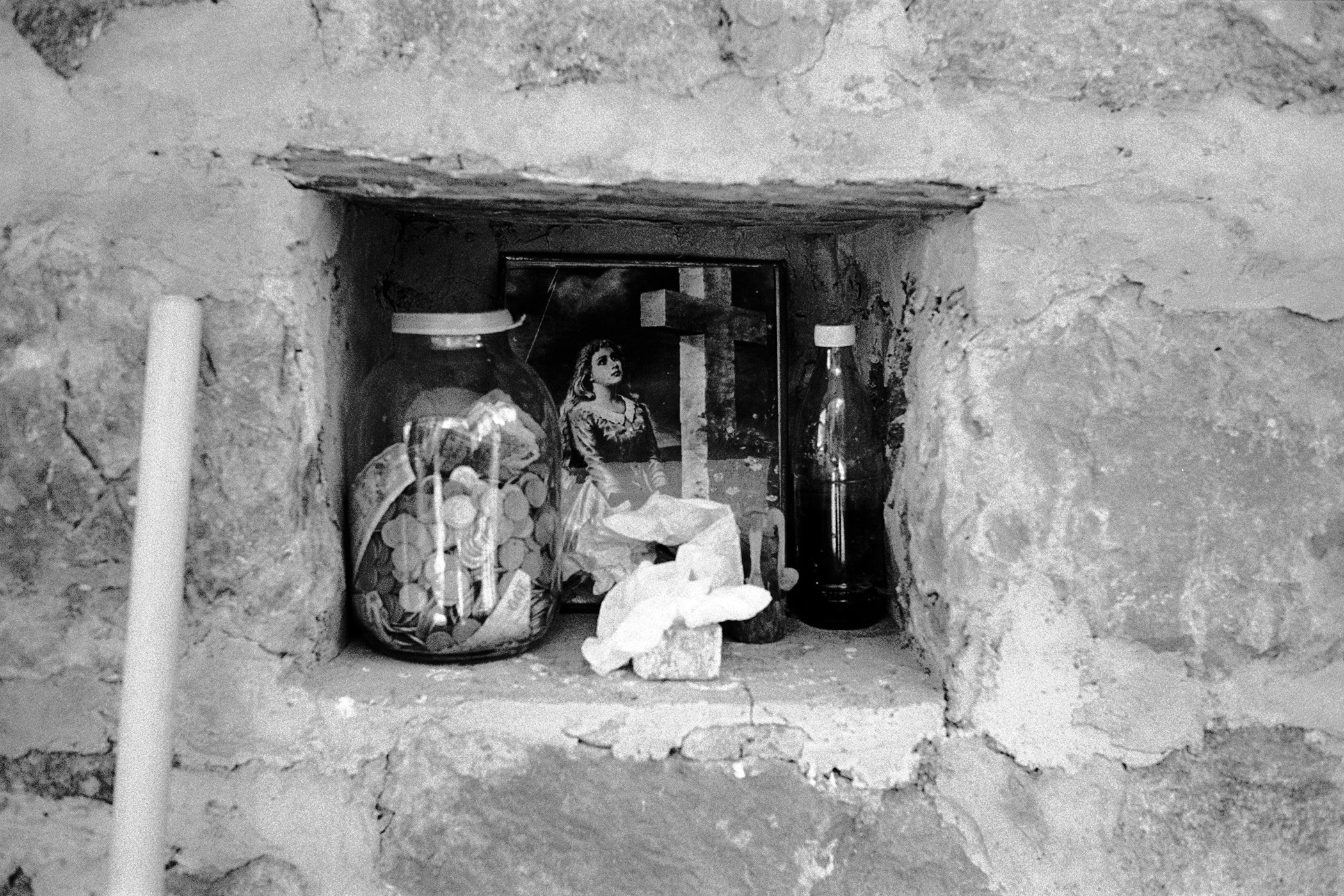

We take our skis off and walk through this crumbling settlement until, just behind some scruffy houses, we come across a freshly repainted place of worship. Entering through a small wrought iron gateway we discover a serene haven of impeccable cleanliness. Under a big, hundred-year-old tree, tables and chairs are set out so you can feast with your creator. Along a lime-bleached wall, icons with familiar faces of Christian saints shelter under alcoves; while an image of a young girl kneeling down in front of a cross seems to remind devotees about their obligation to charity: offerings can be made directly into the big glass jar placed neatly in front of the scene. This religious symbol, immaculately maintained in an otherwise dilapidated village, reminds us just how strong Georgian faith is.

Time to leave the mountains and head back to Tbilisi. Two hours on the road is all it takes to get us back to the heart of the capital. In the warmth of spring, meandering through the maze of the old quarter streets with the haphazard buildings and squares where dominoes players gather seems like a real journey through time. What a joy to get lost then pop out onto a huge courtyard between big buildings. Games for children, little tables and chairs set out for locals to share picnics, laundry drying in people’s windows, petals of almond trees fluttering through the air, stripy stalls, wine merchants, almost invisible bakeries where the bread is bought through little doorways at floor level, structures cracked by earthquakes, pious women adjusting their head scarves before they go into tiny little churches, children tearing down the street with a rugby ball, parishioners being blessed by the hand of the priest who crosses their way…Georgia leaves a subtle taste in your mouth, one of a country with eastern and western flavours mixed together, crimped by huge mountains with limitless possibilities- a friendly country with subtle wines and varied, tasty cuisine. It’s a place with incredible riches whose many different faces are worth infinitely more than just a ski trip.