Swiss ambassadors Arnaud Cottet and Loïs Robatel’s foray into Iran accompanied by Jag and cameraman Alex Amiguet. A trip to the fertile crescent where man first domesticated an animal as livestock : the goat. An expedition to the home of livestock farming, where the massive mess all began, basically ending paradise on earth.

A landscape as dry as a tortoise’s neck. Mounds one after the other, not one of them standing out, or perhaps they do once your eye has been sufficiently trained to draw some nuances out of the monotony of the landscape. Between the low rocks, the outline of knolls and tiny structures eroded by the wind appear on the desolate horizon. Your eyes scan the mounds along the way, searching through the little dents for the shape of an arch or any kind of vestige testifying to the passage of man through these ancestral trade routes.

Rocking to a musical selection with Jamaican flavours, the minibus driven by Arman drives towards Ispahan. Alex, sitting by his side chooses the music while he watches the deserted landscape unravel, stretching out from Tehran right up to the foothills of the Hindu Kush. Behind him, Arnaud, Loïs and myself, although familiar with this endless space, are just as taken in by the mirages appearing on the horizon. On our right, a few dozen kilometres behind the undulations of this terrain are the Zagros Mountains: an enormous mountain range stretching out over 1500km from Turkish and Iranian Kurdistan in the north then along the whole Iraqi border before plunging down towards the Persian Gulf. Arman is driving us right into the heart of it. After a one-night stop in Ispahan, we set off directly towards Fereydunshahr, the last town anchored to the mountains.

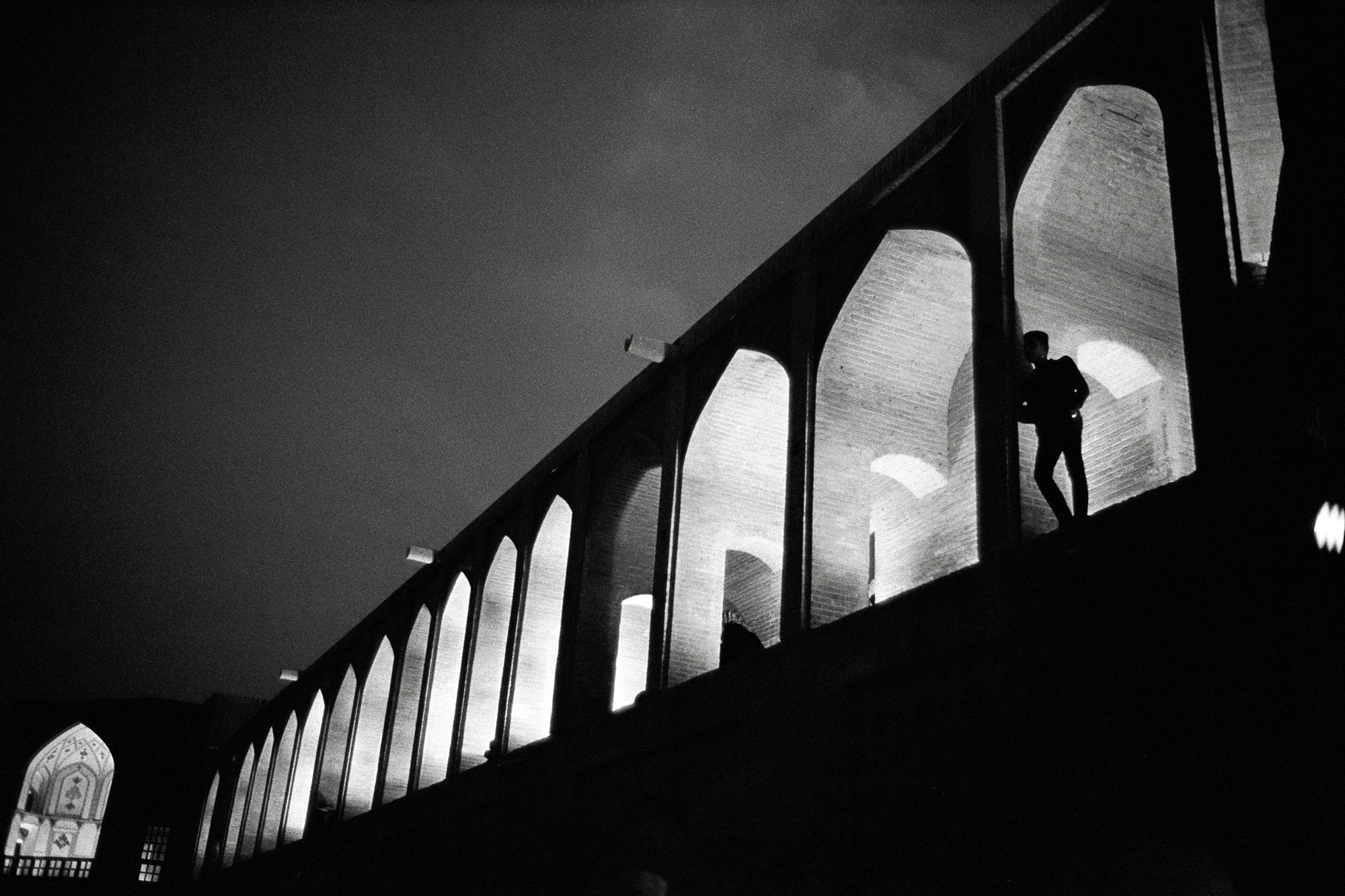

Isapahan and the famous Si-o-se Pol bridge whose 33 arches filter water from the Zayanded rud River (“river that gives life”) and where discreet encounters take place in the alcoves of the upper level. It’s never-ending hide and seek along these arches erected in 1608 by the Armenian general Allahverdi Khan. The Iranians hang out here with friends and family. Girls and boys exchange glances, nudge each other while flirts and desires weave in and out of the centuries-old walls of this jewel of Safavide architecture. Here a group of effeminate young men sing and cluck like lovebirds; two women share a hookah as they admire the sunset…The strictness of Islamic law seems distant in this progressive little town carried by its youth and large university community.

Between our arrival at Tehran airport and our walk on the Si-o-se Pol, a handful of hours have gone by. This time period was enough to transport us to the heart of a new world, a tangible east that we’d like to touch the substance of. Ispahan, a name that can transport the imagination back to secular eras: Nagsh-e Jahan square (portrait of the world) with its circumference of 9 hectares; Masjed-e Shāh mosque (Mosque of the Shah), its magnificent dome finely decorated in colourful mosaics seems to facilitate celestial transcendence; Ali Qapu palace (the High Door) whose upper floors were royal receptions from the Safavide dynasty. Here we are, all four of us, tasting a strange snack made of corn and mayonnaise at the very place where, centuries before, polo matches and wild animal fights were rousing the crowds.

The sun was already setting at the end of this February afternoon. It’s time to put the imagination on pause and come back to a basic need, to eat. Finding a restaurant that serves anything other than lamb skewers or kebabs (pronounced kabâbs) has proved to be a testing exercise in modern Iran. After having asked in a few stalls, one of which selling the latest Apple telephones-still no international banks in Iran but lots of the latest Californian tech- we found our spot in a plush restaurant where we could freely sample some of the country specialities. Iranian cuisine is a subtle balance between salty and sweet, astringent and delicate flavours. Âshs (a kind of thick soup), âbgoushts (meat cooked in water with grains, herbs, aubergines, courgettes, cabbage, etc mixed and beaten with eggs and cooked like an omelette), dolmehs (different kinds of stuffed vegetables), khoreshts (ragouts or sauces served with rice), kabâbs, borânis (vegetables normally cooked with yoghurt), not to mention the side dishes and condiments like torchis (vegetables or vegetable vinegar fricassee), desserts, pastries and syrups…The diversity and richness of the Iranian culinary scene forces travellers to step into it, at the risk of never being allowed to leave.

The next day at dawn we hit the road for Fereydunshahr. Just outside Isapahan and with our stomachs begging for mercy Arman stops suddenly. He crosses the road towards an little stall invisible to our eyes trained more for neon signs and comes back with a kind of suspect gelatinous mush. It was a dish called halim made from grains, turkey, sugar and cinnamon. Perfect for starting the day and snoozing for the three-hour journey in front of us.

Approaching Fereydunshahr, the mountains rise up alongside the road and the snow makes its first appearance. The landscape is still just as arid apart from this whiteness that comes closer as we gain altitude. Fereydunshahr is located at 2500m and is a veritable oasis in the middle of all that dryness; there are orchards dotted between construction sites and despite the wintry conditions, you can imagine all the rich vegetation that will arrive with spring. Once we reach town, Arman negotiates our accommodation in two or three sentences, then we go straight out to explore the little resort a few kilometres from the centre.

At the end of a road crossing empty lands, we arrive at a huge parking lot that’s pretty full despite the gloomy weather at the end of which sits a big grey building. Just past that is a big buttress with two drag lifts and two pistes, one of which looks super steep but with next to no skiers given how full the car park is. That’s when on our right we see a swarm of black dresses dancing in the snow. It’s a truly astounding sight. All down the makeshift piste starting at the road and ending 150m lower down, dozens of men and women were sliding down on truck inner tubes with a playfulness worthy of a Fellini of the good old days. They all launched themselves at once on the inflatables for a crazy race and it’s a miracle they didn’t collide with the other members of this joyous carousel sprawled over the piste. The inflatables took chaotic lines at crazy speeds on this little slope. The obligatory cloaks and scarves were all over the place and the farandole of black and white heightened the hypnotic visual effect. Then everyone was shouting, laughing, couples were hugging each other and forgetting, on the way done, the codes of dogmatic religious decency. The magic of the snow has had its effect once again, breathing joy all around itself and there we are sheepish in all our gear, grimacing at the weather while the simplicity of the joys of snow plays out in front of us in a concerto of twirling and exultation.

Stuffed into our bright outfits in the midst of this sombre crowd, we go past the big building that seems to shelter a restaurant before reaching a check point selling lift passes. We had actually just passed the equipment rental place officiating over a whole range of skis and boots covering the whole surface of a place with just a few metres squared. Excited to see foreigners, he showed us his whole treasure trove looking at our skis with the eye of a circumspect connoisseur. In his hidey-hole he had all kinds of equipment and lots of old skis for modern sizes on offer. We share a tea and engage in the mirror of photography, communicating in big gestures while our skis pass from hand to hand to be inspected from every angle.

After the initiation of buying our lift passes, now we had to cross a gate to get into the resort. Iranian resorts are in the mould of a private reserve, they are surrounded by an enclosure and once inside, you are inside a private space. This also allows women to wear outfits suitable for winter sports- without trying to fuse this with what envelopes them in the outside world-which is not always the case in western resorts- and to wear a beanie instead of a head scarf. But beyond style, it’s in the mould of the relationship between this society and the private area. Restrictions in the public sphere seem to have pushed Iranians into shutting themselves off in order to breath. In that way you rarely see big bay windows opening out onto the world but rather grills and curtains on every window.

After two runs in pea soup, a bitter wind and tricky snow, we decide to go and warm up in the restaurant. The menu is simple and uncompromising: rice, mutton or chicken skewers, yoghurt, soda. The big hall of the refectory is filled with noisy, joyful tables, and most seem to be women. Despite our foreign faces and our flamboyant adornments we seem to pass relatively unnoticed. A few photos here and there with the young ones excited by too much sugar but apart from that the Iranians seem more considerate than intrusive. On the way out we bump into a very pretty young girl wearing a big saucepan. The crazy inner tube riders come here with a huge array of camping gear and the bad weather forced them inside, normally picnics kick off on the sides of the luge piste. Iranians love picnicking and during nice days in the holidays all the green spaces and sides of the roads, or motorways are taken over by families lying on rugs with their portable barbecues.

The next day, we come back to the resort under a big blue sky. We check out some great off piste options from the main drag lift- there is a second aimed at beginners, as well as a little chairlift servicing a zip wire for intrepid thrill seekers. A few minutes on our skins and we gain access to the superb slopes on the edge of the area. In the opposite direction is a seemingly endless sea of mountains stretching out to the west. Nonetheless, we set off to the east to the road that links us toward a more familiar world. Once at the bottom, a little skin takes us back to the starting point. The snow is fantastic and we spent the day exploring and tracking different bowls nearby.

After two beautiful runs we have our own picnic at the bottom of the lift. We had a great day and since it’s Friday, a day off in Iran, the area is full of tourists. While enjoying the delicious cheese brought over by my Swiss colleagues, we were able to leisurely enjoy the joyous skidding of Iranians on a jolly. The overall picture is basically the same as what we see in out resorts: gangs of young women giggling and frenetically forcing themselves on the world through selfies; champion last-minute high speed turns just before the drag lift; beginners in delicate positions defying gravity; fathers carefully initiating their offspring in the pleasures of skiing…All fusing together like Saint Vitus’ dance where all the crazily disguised people had invaded the piste.

After tracking the first couple of the closest runs, we take advantage of the afternoon to admire once again the incessant inner tube ballet before heading back to the fold. On the way back Arnaud asked Arman to explore the road that sinks down further into the never-ending mountain landscape. We hit a village here and there sleeping under the snow but otherwise the road seemed to never stop heading across other valleys. The possibilities are amazing with really nice slopes nestled between great alpine terrain but the approaches were long and you’d have to come here in expedition mode with bivouac equipment to really go and lose yourself in the remoteness. At the top of a col, with the mountains stretching out toward Iraq as far as the eye can see, we turned around without knowing where to go a put our skis the next day.

To be continued…