In early June 2023, Matthias ‘Super Frenchie’ Giraud did his thing on the north face of the Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey (4108m). Skiing a super steep line then jumping off a large serac, opening his parachute to end up smoothly on the glacier below.

The OG plan was to tell the story of this feat from the dual perspective of Matthias own vision, his GoPro POV with the added emotions, and that of his friend and film-maker Stephan Laude, who was as always behind the drone camera that day and saw the scene, like so many others he has filmed, from his outside position on the Col de Peuterey.

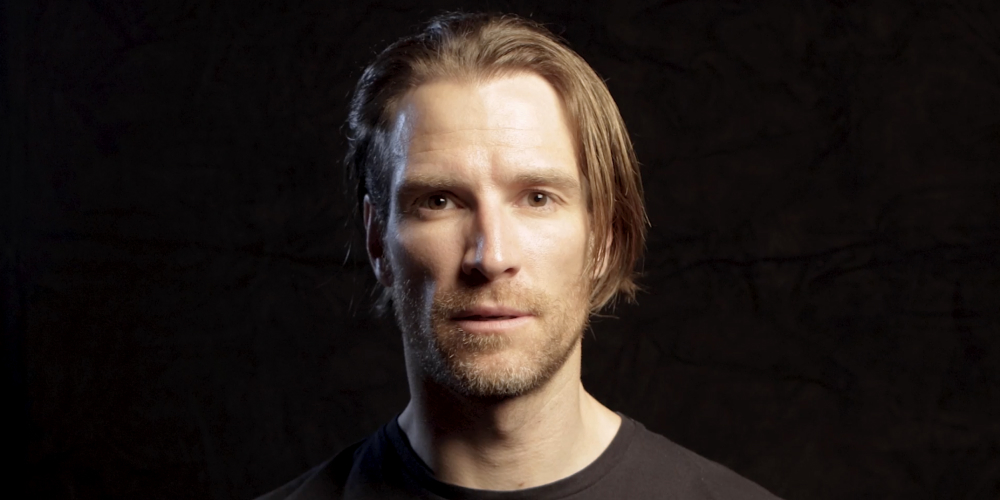

And then when you meet Matthias over a coffee (after reviewing his TedX presentation “How to Stick Your Landing” and his film Super Frenchie), you immerse yourself in his philosophy of life, and change your perspective. Because what’s most fascinating about this extreme snow enthusiast, over and above his skiing prowess on “impossible slopes”, is what he tells us about ourselves, skiers in frantic pursuit of an all-consuming passion.

When I explained to Caroline (the mother of my children) who I was going to interview this Monday in Paris, she raised an eyebrow and said “ah, great, a guy who hits a cliff on ski base and spends 3 days in a coma just before the birth of his son, he’s probably a really clever one”. It’s with this acerbic remark in mind that I wait for Matthias Giraud with a coffee in the sun. “I’ll be there in 10 minutes, I’m helping a guy who’s had a problem in the street, we’re waiting for the fire brigade.” A guy who’s just arrived in Paris to help people in distress does not sound that egocentric, and probably has something to tell me about life, beyond his equivocal propensity for jumping off cliffs.

Here comes Super Frenchie

But let’s take a paragraph or two to put him in context, waiting until he’s finished with his urban rescue. Matthias Giraud is originally from Evreux (50km west of Paris), has lived a fair bit in the south of France (he trained with the Nîmes city ski club and describes himself then as a “tourist”) and has skied a lot around Megève, where his parents had a chalet. He moved to the US 20 years ago to pursue the West Coast snow as much as (or even more than) his studies, and quickly inherited a nickname that has stuck with him to this day. “I was doing a big air competition, and a guy put a French flag around my neck. I did a superman front flip and when I went back for the 2nd run, the commentator announced on the microphone Here comes Super Frenchie”.

His father is a late skier (with a Chamonix-Zermatt haute route under his belt though) who did quite a bit of parachuting in the special services commandos, while his sister passed her pilot’s licence at 16. In short, a pretty aerial family, and Matthias is no exception. He went for his first aerobatics flight at the age of 11, has always been into big freeride jumps, and discovered ski base in “Pushing the Limits”, the 1993 movie with Mark Twight in the role of Xigor Copeland. “I knew straight away it was my thing”.

His meeting with Shane McConkey in 2005 really put Matthias on track and showed him the way. He took up base jumping in October 2007, and started ski base shortly afterwards, in February 2008. A true legend of freeride and base jumping, and one of the first Redbull athletes, Shane McConkey was himself inspired by Jean-René Gayvallet, who was the first to mix freeride skiing with base jumping, notably by jumping from the Eiger in the early 90s. Proving that life (and skiing) is a cycle, a few years ago Matthias did a double backflip in front of the Argentière glacier, which is said to have inspired Jean-René to take up ski base again at the age of 60.

Existential maximisation

When Matthias finally comes and sits in front of me, I start straight away with the question about that egocentric conceit that makes my wife cringe. He replies by quoting Carl Jung (it’s a good start): “The greatest tragedy of a family is the unlived life of the parents”, and there I am, more naked in the arena than a gladiator thrown to the lions. “What kind of example do you want to set for your children? That they should fall into line, and live only for others, forgetting themselves until they have no real fulfilment? Fulfilment comes from within, and when you’ve found what you love most, what allows you to turn your dreams into memories, you need to have the courage to live your life to the fullest.”

For Matthias, this fulfilment means jumping off impossible slopes on skis. It’s more than a job, more than a passion, for him it’s a true vocation. And even if (as in my case) you can’t necessarily put yourself in his shoes, his philosophy can’t help but speak to snow lovers. Because each of us, at our own level, has a non-negotiable need for snow to satisfy. “If I negotiate on this, I’m betraying myself. It’s not acceptable, and the person I spend my life with wouldn’t accept it either. Of course I always try to balance my actions to maximise my existential potential, and to do so you have to take other people into account. Because if you’re only into your personal passion, there’s only one dimension to your life. You have to honour your passions, whether it’s your vocation or the people you love. It would be selfish, there would be a huge lack of respect if I didn’t prepare myself in a very meticulous way, if I didn’t have this assiduous spirit of analysis to approach my projects.”

Concentration, visualisation, execution.

When he sets off on a ski base mission, Matthias follows an strict process of concentration. Scrupulously checking his equipment, from his ski bindings to his parachute extractor, helps him to get is mind set on his jump. He moves on from the observation phase that comes with going up a mountain surrounded by majestic elements, to get into the action by concentrating on an unchanging checklist.

Once equipped, Matthias visualizes his turns, his route, the sequence. He works in segments, like for a freeride line. “I’m going to ski to this point, from point B to point C, and the jump it might be the point F. You link it all up. It’s a logical approach, which respects a precise sequence.”

Planning is essential in ski base, which mixes and multiplies (even going exponential) the hazards of two high-risk sports. Matthias always has a main idea beforehand, but conditions change all the time, and he also has a plan B, C and “maybe on the spot it will be plan E”.

For his jump from the summit of Mont Blanc back in May 2019, he scouted the spot by helicopter with his team, then took advantage of the 2-day approach tour to study the conditions. He can also count on the advice of his guide, Alexandre Perinet from Megeve, and film-maker Stefan Laude, himself a paragliding instructor and expert aerialist. But as he repeats, “you never know until you go”. Snow and wind are capricious and volatile elements. “That’s the hardest part. All our fears come from our uncertainties.”

Matthias had prepared particularly well for the Mont Blanc jump. “It was my first ski base serac, my first high-altitude jump, and it was very complicated.” It was a seminal jump, taking him one step further. “If I hadn’t done Mont Blanc and the Aiguille du Gouter [in June 2022], I wouldn’t have been able to go for Peuterey.” Peuterey is a very steep face, making for very technical skiing. All the more so that day, with blue ice hidden under a thin layer of snow that barely allows to hang on and turn. And ice reveals itself after the first few turns, the best ones, for which Matthias has been roped up. “That’s real skiing, you have to adapt. It was magical to be able to ski down a steep slope and ski base in such a high alpine environment.”

This achievement was hailed by his masters, Jean-René Gayvallet, who congratulated him at length, and for whom Peuterey is an obvious ski base face, as well as one of the skiers who premiered this north face, Anselme Baud himself, who skied there with Patrick Vallençant in 1977. He comments on the YouTube video, “well done, and this way we avoid the more technical and dangerous part under the seracs”.

Ski base is skiing XXL

“For me the top is the best part of the line,” confirms Matthias, who feels that it was already quite technical. “I know how to ski the steeps, but I’m no Vivian Bruchez. The advantage with ski base is you get to ski the most aesthetic part of the line, and then you just jump and fly. When you land at the bottom of the glacier, that’s quite a feeling.

While Matthias called his partner, his son and all those close to him who knew about his jump to reassure them, filmer Stefan Laude put the drone down and could also rejoice. It’s in the box. “I’m holding my breath throughout the whole process, because I’m under two major stresses. It’s a one-shot every time, so I can’t miss, and then of course it has to go well for Matthias. The film crew is often the only live witness… I remember the reaction of Shane McConkey’s cameraman in the chopper on the day he died.”

North face of this Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey is a face that Matthias looked at for 12 years, “it scared me so much that I couldn’t ignore it any more, I was obsessed. It was probably the face, with the jump from the summit of Mont Blanc, that scared me the most in terms of my mental preparation. I’d wake up sweating in the middle of the night. It’s hard work”. Because ski base is a game of life and death, especially on a face like this, with the steep ice and the seracs adding to the atmosphere. “Nobody wants to play near the seracs,” explains Matthias. “Shane McConkey jumped some in the Yearbook movie by MSP, Mark Twight also jumped solo, but it’s rarely done, you don’t usually go near seracs, there’s something unknown about them.

Nobody is born humble

For a jump of this kind, the commitment and the decision are made at the start, then it’s a straight line and there’s no turning back. With the parachute in his hand to open as high as possible, Matthias manages his safety margin. “That’s when you need to have that respectful, humble approach to maximise your survival. And nobody is born humble. Like all skiers, we go through these phases of arrogance. But you never forget hitting a cliff, I think about it all the time.”

Matthias doesn’t use the mountain as a springboard, like the pioneer of ski base, Rick Sylvester, who was James Bond stunt man for The Spy Who Loved Me in 1977.

Matthias’ aim is above all to ski a whole line, taking advantage of the parachute to avoid abseiling. “For me, ski base is skiing XXL. It’s like being towed by a jet ski into a wave that you couldn’t catch paddling. That’s surfing in its own right, and this is skiing in its own right.” You have to control your skis from start to finish, you have to be able to jump, stay stable, and of course control your skis in the air because there’s a lot of relative wind until the sail opens, as Hermann Maier showed when he took off in Nagano.

Mountain inspiration

After this line, Matthias still has that special look at the mountains, a look that’s different from that of a simple skier, more aerial. He spotted Peuterey’s north face while travelling to Hellbronner for a movie project with PVS, and he’s always on the lookout. “The more projects I do in the mountains, the longer my list grows, especially in the Alps, which I find particularly inspiring. They’re mainly firsts ski base descents, there’s still a lot to do, because there aren’t many of us.”

Having this multi-disciplinary approach allows Matthias to discover, elaborate and break new ground. “That’s what Boivin did. He mixed base jumping, paragliding, steep slopes, climbing, mountaineering – he was the ultimate mountain man.